Ten of the 56 works shown at Valley House Gallery, Dallas, 2021. Installation and photograph by Ben Bascombe.

Ten of the 56 works shown at Valley House Gallery, Dallas, 2021. Installation and photograph by Ben Bascombe.

Moonlight with Black Bowl

“The moon is created by the cloud, the oozing green mud-made cloud, which resides just above the bowl. Why a bowl if not to hold the moon?”

From “Mary Vernon’s Open Places” in Emerita: A Retrospective of Debora Hunter and Mary Vernon, Curated by Sofia Bastidas, 2018, Pollock Gallery, Division of Art, Southern Methodist University.

Fields at Mora

Dennis Boatright, 2017

As Atlas lay down a piece of the globe

A remnant became a totality

Heartened was I to have stumbled across it

With its yellow patch of the sun’s memory

And the blue of the ocean’s refrain

But the presence of the grass

Oh how it presented its secrets to me

As If I were the only one who could see them

So I promised myself that one day I would return

To lie under the dark presence

And become a brother of the earth there

With the gray blue sky as my forever view

In the wondrous and final grasp

Of the fields at Mora.

Moon at Caprock

Dennis Boatright, 2018

The orb

Shadowed and pregnant

Is a dweller we all know

She is the origin, the maternal

Of all

Marking her way by taunting us

Blurred today

Bombastically orange sometimes

Recedingly blue from her perchless perch

Dangling like a great opening

A door to our fate

Imbuing the chaos below

An emotional mother is dangerous

To her children

And we are come forth from her milk

This somatic treasure that allows

The seen to become the known

Like the way the hills pour onto the fields

But not really

For how can they be separate or

Even blended

When the essence of both

Is born of her eye

And makes me wonder if night is her day

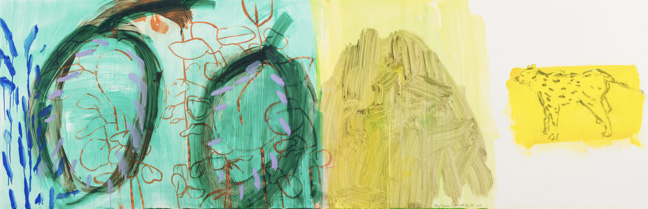

Island with Bay Cat, 2018

By Frederick Turner

It’s not that Mary Vernon doesn’t have an axe to grind; she does, but it’s not the ordinary kind, where the Artist’s Socially Responsible Message overwhelms the poor wretched image. It’s that the axe she grinds is one of sheer astonishment at the beauty of the world and, even more, of our perception of it if we open our eyes. Her pawings or draintings are like the very pieces of the world they represent: not the way a photograph is like them, but the way our real amazing jelly eyes grab them and try to make sense of them. They look as if they’d been there forever, with their quirky textures and odd bits of brightness and splotches and drips and smears and all. These lives are not still, but dancing with light and color—she is one of the great colorists of the world, but it’s all done with such insouciant mastery that one doesn’t feel got at or advertised to. She can be as glum and drab sometimes as any odd dim afternoon with some impending revelation or sudden retrospective insight in it.

Vernon’s peculiar virtuosity—or rather the way she rides it—is a sort of solution to a big contemporary problem among good artists. There’s plenty of virtuosity about, and artists want to be singular. Do they just throw out their amazing gift, given to them for the solace and enlightenment of the world? Do they sneer at it while exercising it? Do they coyly disguise it? Do they show it off as a sort of conjuring trick, with an intellectual explanation? I’m not talking here about the usual bright artist who never bothered to learn virtuosity in the first place, and can get away with that these days.

No, the really good artists around now, of whom Vernon is one, take their virtuosity as a gift, and give it away as a gift to our powers of sight and our capacity for joy. They don’t take it entirely seriously—it’s like dancing with a god, or wrestling with an angel—but they respect it too. They’re on such good terms with it that they’ll josh it a bit so it doesn’t put on airs. Mary’s outrageous sense of humor is everywhere in her work, but it’s not lightweight—it’s as serious as a Shakespeare comedy. And what Mary means by “drawing” is, I think, also more generally the virtuosic power of revelation, the sweet shock of the wabi-sabi of the world, its messy amazingness, its cockeyed calm. She’s a nature artist, one could say, but for her the human, technology and all, is still nature naturing, inventing odd aspects by which it sees itself anew.